The Roadmap: How to Train Your MEV

Introduction

MEV (Maximal Extractable Value) is a practice of block builders using their right to order transactions in their blocks at their discretion to insert certain transactions in certain positions to get additional profit. MEV is typical to all network with large economic activities happening, the notable examples being Ethereum and Solana.

While being helpful when used correctly, MEV might become a significant centralization concern in all today’s crypto networks. In this article, we’ll review the technologies in the Ethereum’s roadmap targeted at minimizing risks from MEV.

What’s MEV?

Let’s explore two usual MEV-extracting strategies done by block builders:

Non-Toxic MEV—Arbitrage

As the simplest example: on Uniswap, 1 ETH costs 1500 USDC, and on Sushiswap, it costs 1510 USDC. By buying and selling ETH on these two platforms, the arbitrageur can earn 10 USDC from every ETH bought, before the liquidity in these two pools reaches equilibrium.

Block builder creates an arbitrage transaction and inserts it before anyone else’s transactions to prevent anyone from using this arbitrage opportunity before them. This way, the block builder received profit from this arbitrage in addition to the block reward and priority fees. All the other transactions in this block will have the same ETH price no matter which pool they use. It’s a win-win!

However, this is not the only type of MEV used by builders. The aforementioned technique is called “non-toxic MEV,” as it doesn’t target a specific user, but the entire liquidity in the network. The another type, respectively called “toxic MEV,” is also known as a sandwich attack.

Toxic MEV—Sandwich Attacks

-

Suppose I want to buy 1 million USDC worth of ETH on Uniswap. I create such transaction with 1% slippage (slippage is the maximum difference in price at which I’m still willing to make a trade). \

-

The builder that creates the next block sees my transaction in the mempool. They create a transaction that buys the maximum amount of ETH that does not increase the price more than by 1% and insert it in their block. Then, they insert my transaction and sequentially their own transaction that sells ETH bought from their previous transaction. \

-

Because my trade is large, it increases ETH/USDC ratio in the pool, which is in turn abused by the block builder. From the point of transaction ordering, it looks like that:

— they buy ETH cheap, making it more expensive;

— I buy ETH for high price and make it even more expensive;

— they instantly sell that ETH for the new price, returning the price to previous values and receiving the profit at my expense.

The name “sandwich attacks” appeared from the fact that a victim’s transaction is inserted between two attacker’s transactions, making it similar to a sandwich.

How Does MEV Work?

To understand how MEV is possible, it’s important to break down block building in today’s Ethereum.

In Ethereum PoS, a validator, which turn it is to propose a block, can select the contents of their block themselves. The default logic for transaction ordering in a block is to simply take all transactions in the mempool with a base fee larger or equal to the block’s one, prioritizing those with largest priority fees.

However, the validator can change the building logic to their own. They might be interested in doing this to perform on-chain tasks that will maximize the validator’s block profits. For instance, execute an arbitrage in multiple swap pools or, as we’ve said earlier, sandwich attacking other users’ swap transactions. These actions, performable only by block producers in their blocks, are the Maximal Extractable Value—MEV.

An MEV strategy finder is a specialized software that has to be written by whoever wants to collect MEV. Not all validators can afford to develop a complex stack to find extracting strategies. Moreover, the most validators don’t have enough liquidity for MEV strategies to become profitable. This led to an inception of specialized MEV builders that the validators connect their nodes to.

This de facto created the Proposer-Builder Separation in the network: now, the ones who propose the blocks, and the ones who build them, are the separate entities. The former have stake to propose the blocks, the latter have specialized software and liquidity to implement MEV strategies.

MEV’s Centralization Concerns

It’s obvious that the validators started connecting their nodes to the builders that give the most rewards. As this reward rate fluctuates, the relays have appeared—some kind of builder “aggregators” that automatically choose whoever proposes the most pay for the block. This caused the block production to quickly get into the hands of a small set of sophisticated building actors.

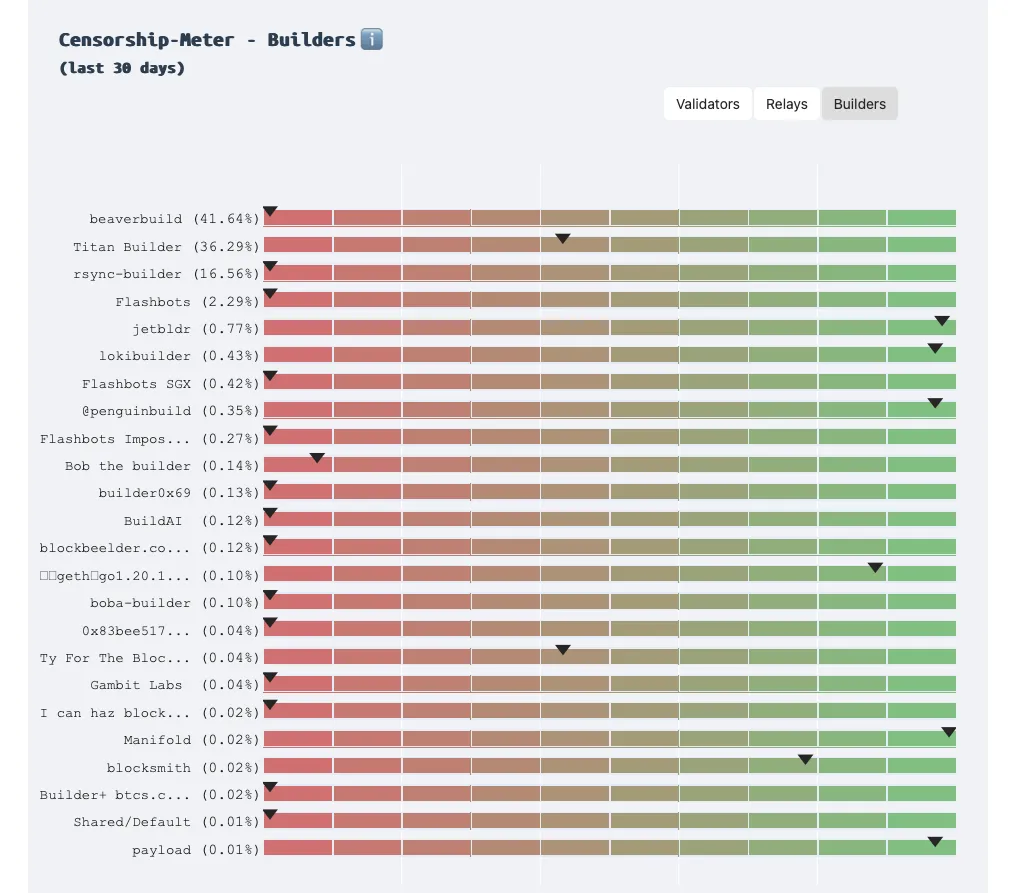

Source: http://censorship.pics/

As we can see from the statistic, at the time of writing, three builders control 94% of the block production! Two of them comply to the OFAC sanctions, which means that transactions such as Tornado Cash take much more time to be processed by the network.

It became clear that the Proposer-Builder Separation has to stay in the network, as block production became a very computationally intensive task due to MEV strategies, but the proposers still have to stay as distributed as possible. However, centralization must still be mitigated.

Mitigating Centralization of Building

Inclusion Lists

As we’ve mentioned above, a significant portion of today’s block builders comply to the OFAC sanctions. This means that they do not include transactions involving addresses in the blacklist of the United States’ Office of Foreign Assets Control. Essentially, these builders censor the network participants that were considered malicious by a government agency.

In the future, these censorship precedents may grow even larger, presenting a significant threat to the credible neutrality of Ethereum. Imagine having your transactions processed an order of magnitude slower because you did not complete some government’s KYC!

This is why Ethereum community is working on Inclusion Lists. Inclusion List is a set of transaction hashes specified by the block proposer that must be included in the builder’s block on this slot in order for it to be valid. The block proposer isn’t aware of sanctions and censorship, so they include any transactions they consider worth adding (the actual rules vary by implementation). The block builders, in turn, would have no option not to include transactions specified by the proposer, as that would make the block incorrect. This way, we can prevent block builders’ censorship.

However, in order for Inclusion Lists to work, the consensus must be aware about the separation of proposing and building tasks:

Enshrined Proposer-Builder Separation

Enshrined Proposer-Builder Separation (ePBS) is a mechanism enshrined in the consensus that delegates the task of building the blocks that will be proposed by validators to the separate entities. The idea is—instead of shady relayers deciding who will build the block, let’s make Ethereum decide!

By allowing fair, equal, and independent of validator set participation of block builders, we assure no single entities receive too much power in the block building. Let’s explore several designs of ePBS:

-

Execution Tickets: This design is specified in the roadmap under “explore” category.

The idea of execution tickets is to make block builders burn their ETH to receive lottery tickets. Every slot, the block proposer generates an inclusion list, and it gets verified by the network. Then, one of those tickets is randomly chosen, and its buyer, a block builder, gets a right to propose a block at this slot, accordingly to the inclusion list.

Essentially, block builders buy a chance to eventually build a block from the network. The price is formed according to the demand in an EIP-1559-like fashion, and the ticket cost gets burned. \ -

Execution Auctions were proposed as an alternative for the Execution Tickets. The difference of this approach is that the slot assigned for the ticket is known in advance, and for every ticket there’s the auction, with the highest bid getting the right to propose the block at a specified slot. \

-

Minimal ePBS is a very distinct approach to understanding the role of builders in the network. In this design, all block builders lock a stake and behave similarly to block producers, receiving the change to produce a block in a PoS-like fashion.

Distributed Block Building

This solution, while being specified in the roadmap, is quite abstract. The idea is to make multiple builders find strategies for a single block simultaneously, via some cryptographic protocol, such as Multi-Party Computation.

This way, no single party can fully decide on the ordering in the block, and the centralization risks are reduced.

Minimizing MEV

While reducing risks from MEV is a protocol-first task, reducing MEV impact itself can be done on an application level.

One of the solutions that Justin Drake suggested is encrypted mempools. Roughly speaking, the point is to make encrypted batch transactions which are decrypted only on the execution. With this system, it’s not possible to attack certain transactions, only to make some work before and after batch execution, which greatly minimizes toxic MEV capabilities.

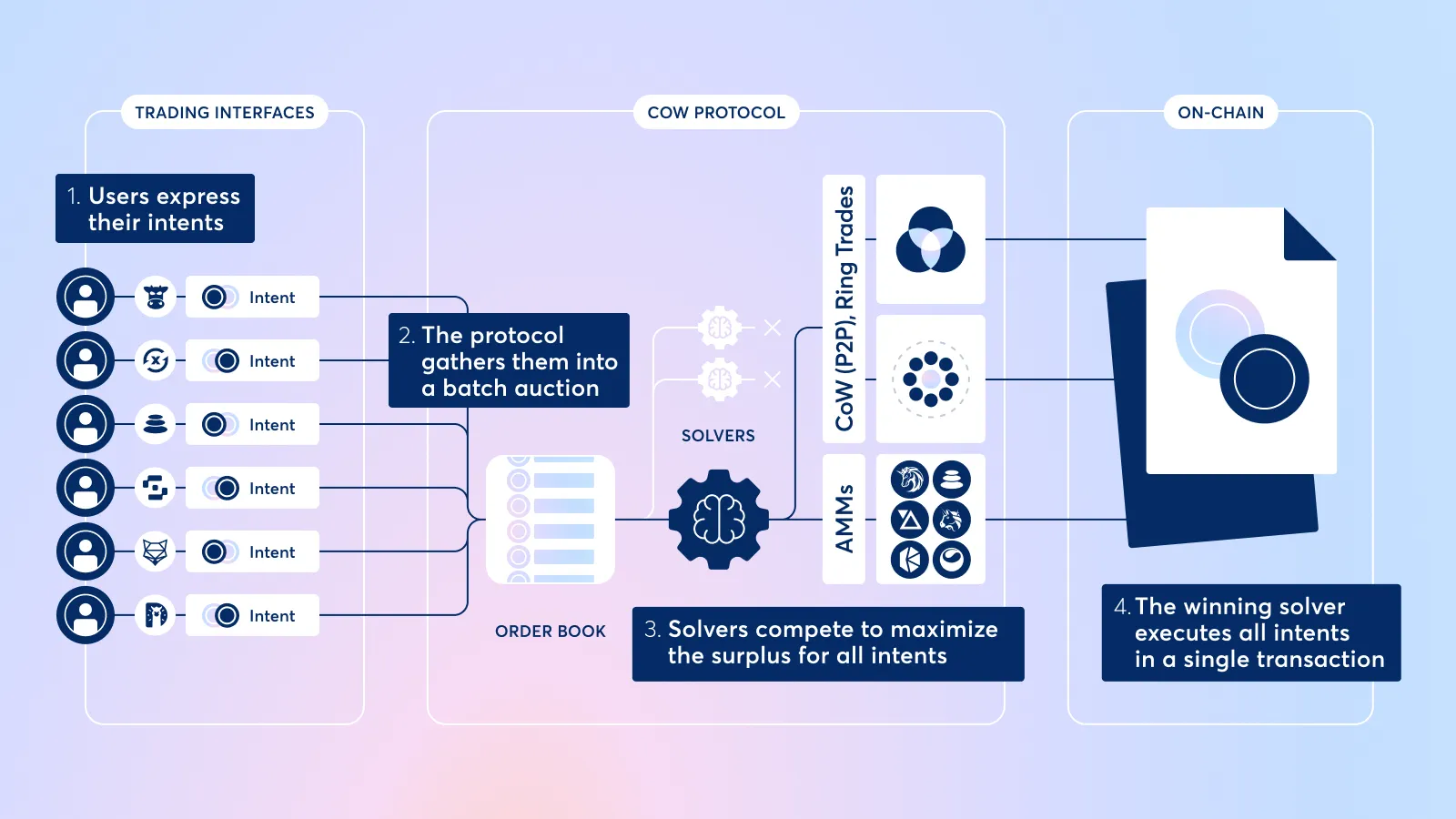

A great example of a protocol incorporating such a technique is CoW Swap. CoW Swap packs all trades in batches and executes them at one time, so it’s impossible to front-run a certain trade inside the batch. Batches can be created and fulfilled by anyone, so the system does not rely on trust.

MEV Burn

While not preventing the MEV itself, it’s worth discussing an interesting concept that could potentially transform MEV into a helpful feature for the network and its users. This concept, known as MEV Burn, has been included in the roadmap under the “explore” category.

The key mechanism of MEV Burn involves selecting a block builder based on the amount of ETH they burn in their proposed block. For example:

- Builder A constructs a block extracting 1 ETH in MEV and offers to burn 0.5 ETH.

- Builder B creates a block with 0.8 ETH in MEV and proposes to burn 0.6 ETH.

- After the bidding period, the protocol selects Builder B due to the higher burn amount.

This approach could potentially benefit users by enhancing Ethereum’s economic model. Currently, Ethereum’s economics operate on a supply-demand principle: increased block space usage leads to higher fees and more ETH burning, potentially resulting in deflation. Conversely, lower usage can lead to inflation, encouraging spending.

MEV Burn could improve this model further by tying the burn rate not only to gas usage but also to on-chain economic activities. As more trades, loans, and other transactions occur, MEV opportunities increase, leading to more ETH being burned. This creates a feedback loop similar to the current gas-based model but more directly linked to actual economic usage by users.

Theoretically, this system could maintain deflationary pressure on ETH even with moderate gas usage, provided there’s significant economic activity. This enhancement could potentially strengthen Ethereum’s position as “ultrasound money” by more closely aligning its monetary policy with real economic activity on the network.

Conclusion

MEV remains a complex and evolving aspect of Ethereum. While it presents challenges such as potential centralization and unfair exploitation of user transactions, the Ethereum community is actively working on innovative solutions to mitigate these issues.

The discussed solutions showcase the Ethereum community’s commitment to maintaining a fair, decentralized, and efficient network. As the ecosystem continues to evolve, it’s clear that managing MEV will play a crucial role in shaping the future of Ethereum.

The ongoing research and development in this area underscore the importance of balancing innovation with security and fairness in decentralized systems. As these solutions progress from concept to implementation, they will likely have a significant impact on the blockchain landscape, potentially setting new standards for how networks handle transaction ordering and value extraction.

Thank you for reading.